The Institute for the Future’s Governance Futures Lab and the National Democratic Institute gathered a group of global scholars, activists, elected officials, and experts on democracy and governance in a series of workshops to explore, critique, and generate compelling visions of democracy. The goal of these visions is to inform and inspire those who are working to protect, strengthen, and expand visions and practice of democracy in the 21st century and beyond.

Overview

Democratic institutions around the world are locked in a generational-scale battle with the forces of authoritarianism, theocracy, and oligarchy. For democracy advocates, the focus has, understandably, been on protecting existing democratic institutions and norms from anti-democratic insurgencies, and the toxifying effects of misinformation and corruption. However, a rear-guard defense is not sufficient for democracy to thrive and evolve past this latest crisis.

This collaboration between the Institute for the Future’s Governance Futures Lab and the National Democratic Institute is intended to contribute to the ongoing global efforts to inspire people to protect, strengthen, and expand visions and practice of democracy. Consisting of a series of engagements with a group of global scholars, activists, elected officials, and experts on democracy and governance, the goal of the workshops was to explore, critique, and generate compelling visions of democracy. Those visions will inform those who are working to make democracy viable in the 21st century and beyond.

This synthesis report consolidates the visions and strategic insights produced at the workshops.

“When something of massive consequence happens that no one predicted, we often say it was simply unimaginable. But the truth is, nothing is impossible to imagine. When we say something was unimaginable, usually it means we failed to point our imagination in the right direction.”

— Jane McGonigal, Institute for the Future

Methodology

Foresight is a set of frameworks, methods, and tools that help us think the unthinkable, in order to identify new opportunities and risks that require different actions in the present. These expert workshops were designed to analyze current conditions, understand alternative trajectories of change, and generate emergent insights and visions for a thriving and future-ready democracy.

To achieve this goal, we gathered 11 top experts from academia, foundations, government, art and culture, and democratic activism in a half-day virtual workshop on October 26, 2021. Beginning with a two-curve process, participants mapped trends and signals of democratic decline, as well as examples of new paradigms and signals of democratic rebirth and growth.

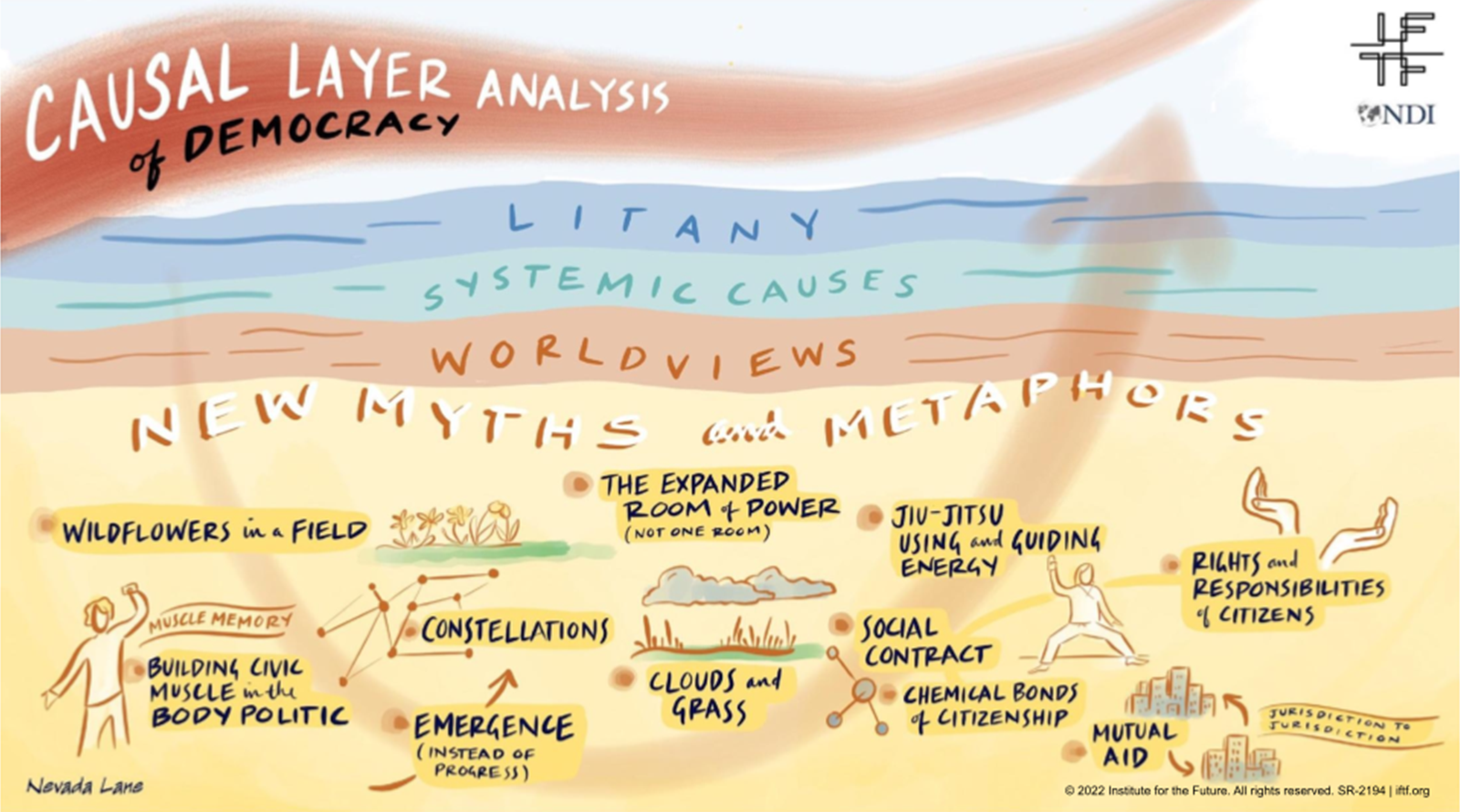

Next, using an approach called Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), the group dissected the underlying systemic causes, worldviews, and guiding myths and metaphors related to the shifting dynamics of democracy. Finally, each expert presented original ideas for new guiding images or metaphors that could act as compelling visions to build a stronger, long-term democratic movement.

With this wealth of analysis and visionary insight, a second virtual workshop was held on November 22 with a select group of experts from the first workshop, along with IFTF and NDI project leaders. This workshop was focused on consolidating and extending the discussion as well as sharpening the insights presented here.

Signals

“The Future” is always an abstract projection from the present. So Futurists look for early stage events, behaviors, indicators, portents, and other evidence of emerging change in the present. These are called “signals” of the future. The signals in this document were presented by expert participants at the workshop. It is not a comprehensive list of signals related to democracy, but if provides a window into what issues are drawing the most attention from this informed group.

Signals of democracy’s decline presented by workshop participants

- The hundreds of new voting restriction laws in the United States after the 2020 election

- Institutional decay seen in survey results showing record low trust in government

- Violent rhetoric and embrace of authoritarian leaders and leadership styles

- The hollowing-out of civil society institutions in Hong Kong after the Chinese clamp-down

- The continued expansion of the use of ‘lawfare’ to silence critics and stifle public debate in places like Turkey, Russia, Hungary, and the Philippines

Signals of hope for democracy presented by participants at the workshop

- The rise of worker movements, union success, and organized action

- High-profile celebrity activism from leaders such as the NBA’s Enos Kanter Freedom

- The rise of republicanism in Barbados

- Stronger voter access laws in many U.S. states

- Grassroots initiatives like the Boston Public Kitchen and Coalition of Community Schools

- Polls showing people are not anti-government, but want government to work differently

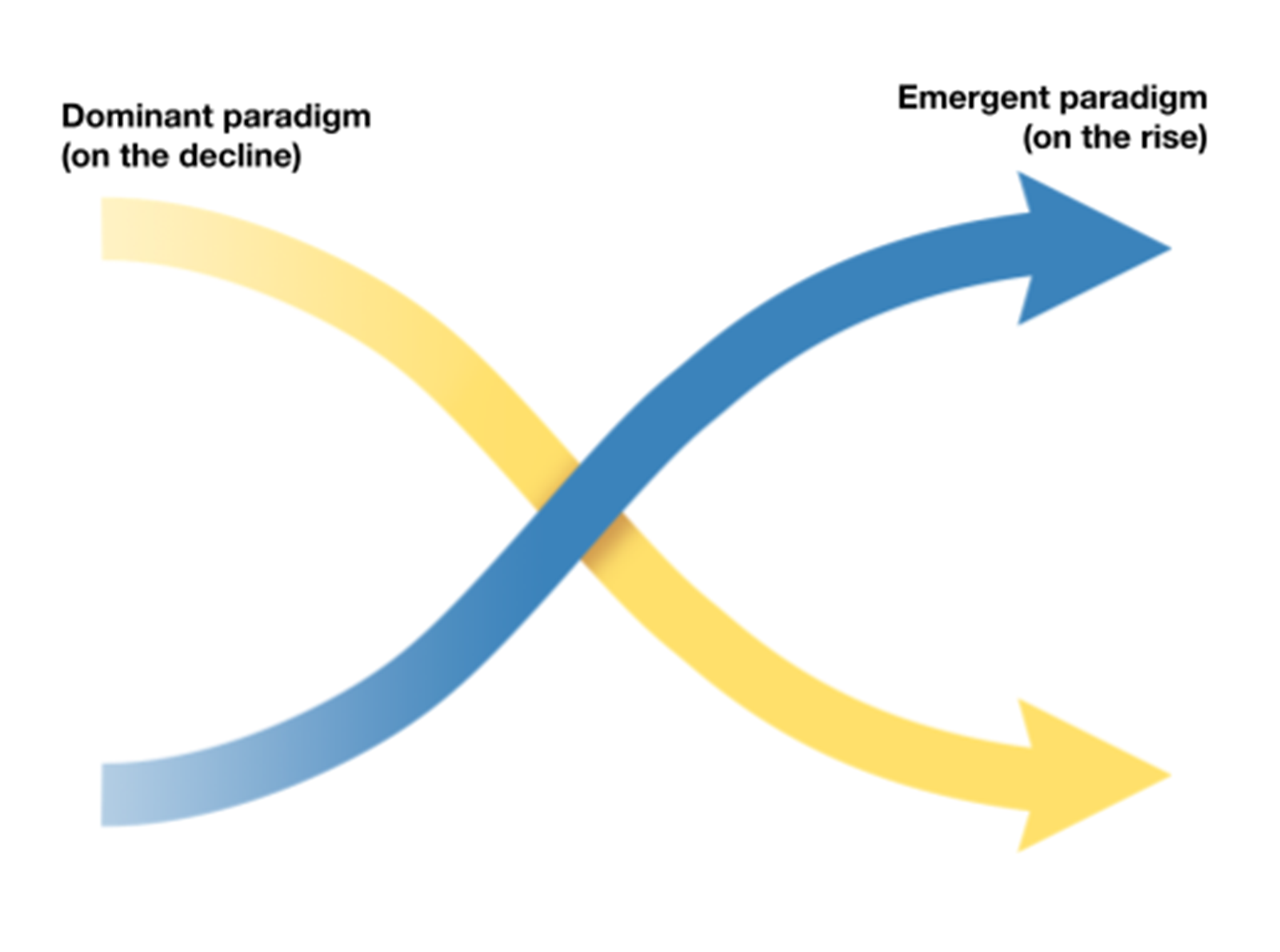

Two Curves

At any point in time there are dominant paradigms on the decline, and new or emergent paradigms on the rise. For example, fossil fuels currently dominate as a source of energy, but renewables continue to grow as a percentage of production and will likely become the dominant form of energy in the next 20-50 years.

As part of the mapping of these two curves as they relate to the forces at work in democracy, workshop participants presented signals of democracy’s decline, as well as signals of emergent democratic movements, behaviors, and technologies.

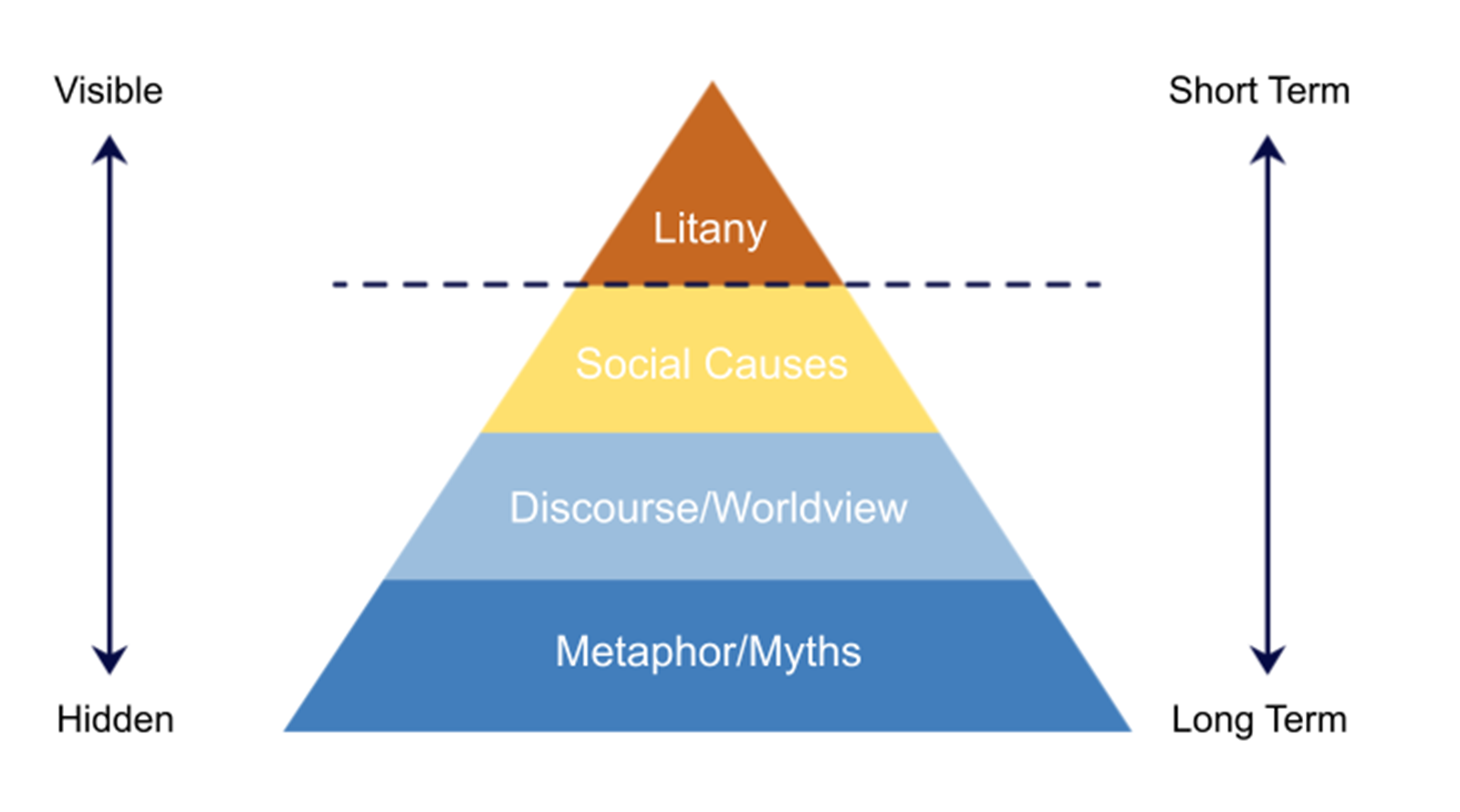

Causal Layered Analysis

Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) is a thought tool to help understand different dimensions of the future and how these dimensions influence our understanding of and responses to change.

It works by breaking an issue into four categories:

- Litany: the array or barrage of data and facts that are disconnected from

explanation or analysis. - Systems: the economic, social, environmental, or other systems dynamics

that are causing the facts listed in the litany level. How can we explain

the reality that confronts us? - Worldview: the beliefs, ideologies, and discourses that define how we

perceive and explain reality. How does the world work, and how do

we know? - Metaphors and Images: the visceral, sometimes unspoken myths

and images that represent deep feelings about reality.

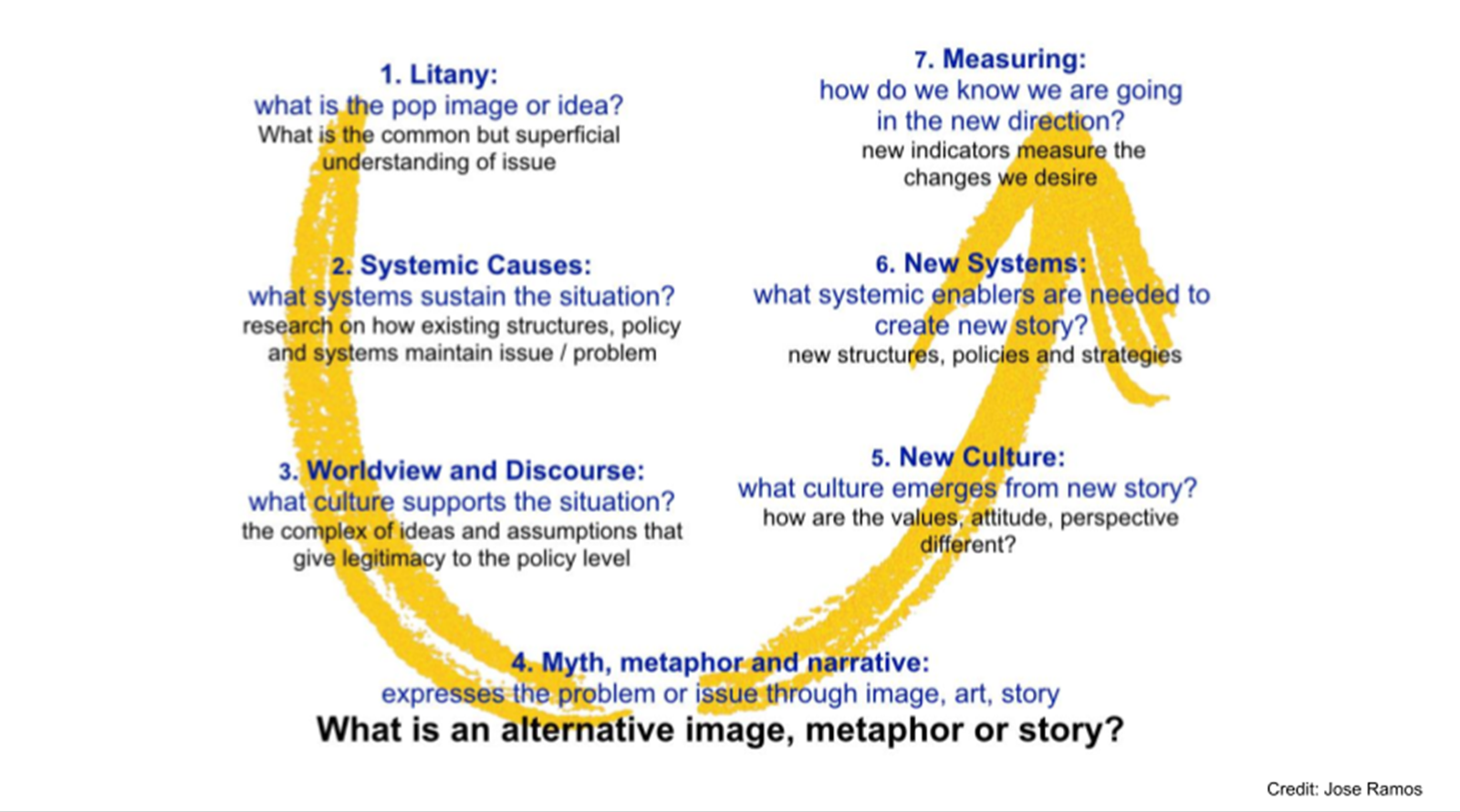

CLA at the Workshop

- The overall takeaway from the CLA discussion centered around the crisis of legitimacy in governing institutions. Two kinds of issues lead to abandoning democratic norms and seeing elections as zero-sum, “fight to the death” battles. The first are structural issues, where power can be consolidated in a single executive, especially in presidentialist systems. The second are perceptual issues among regular citizens, including lack of trust in leaders, and lack of voice at the highest levels. These are conditions of a democratic death spiral, where power is not exchanged peacefully, and fairness is a victim of ruthless pursuit of total control.

- A new or reinvigorated narrative of power-sharing and mutual interest is critical for the future of democracy.

The use of myths and metaphors

- When we use CLA not only to analyze, but also to build an interconnected scenario of a future vision, we begin with a set of the most compelling, energizing, and robust myths and metaphors as a foundation. These are almost pre-cognitive images or feelings that are later reinforced by coherent worldviews, beliefs, philosophies, and ideologies. For example, if we see an image or metaphor of the solitary cowboy staring across an empty plain, we could imagine a related worldview of rugged individualism and possibly the right to the conquest of ‘wild’ lands by bold pioneers.

- Moving up the CLA from ideologies to systems, we would need to find ways to operationalize the worldview in a series of institutions, legal frameworks, cultures, habits, and actions. Using our example of western conquest, individualism needs the recognition of individual rights, and conquest needs legal frameworks of land ownership, personal property, and economies of colonization.

- Finally, if one is to assess whether the system is working as imagined and designed, a set of metrics and data points would need to be generated and monitored. Continuing our example, a person managing the systematic conquest of the American West and its native inhabitants would monitor population numbers, expansion of western laws and customs, movement of goods and services, economic metrics on the ROI of expansion, etc.

New myths and metaphors for the future of democracy

- A host of provocative visions and metaphors for democracy were offered by the expert participants. These included images of diverse wildflowers blooming in a field to expanding the “room” of democracy to allow more voices and viewpoints in the mix.

- But other images and metaphorical domains emerged as well, from the way chemical bonds are formed, to how a jiu-jitsu master directs and re-directs energy flows. Civic muscle and mutual aid also foregrounded the aspect of democracy as an active, on-going process that grows and strengthens when consistently practiced.

- A headline level insight that emerged from the conversation is the possibility that democracy itself is the biggest myth we have. A thorough examination and debunking of the myth that we have ever actually achieved something called democracy might be necessary before progress toward a true democracy is possible.

- An exploration of more deeply developed myths, metaphors, and related commentary will be presented in a later section.

Toward Democracy

Themes, metaphors, and visions of democracy and democratic futures

Democracy is a tool, not a solution

- It can be reasonably argued that we cannot “save” democracy, because we have never actually had democracy. While likely true, history has shown a significant movement, though not always in a direct line, toward governmental forms that function more democratically. Saving democracy is not the goal; rather the continued positive directionality of increased and improved democratic forms is the goal.

- Government itself is an invention, a tool that humans created to make collective decisions and get things done as groups of people. An uncritical drive toward “more democracy” has to be tempered with understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of democratic forms, and a realistic account of limitations and vulnerabilities in the system.

- The themes and ideas expressed below are meant to inform further visioning and refinement of existing governmental forms, and aid in the design of potential new and experimental forms of fair, just, effective collective governance.

“I think the most dangerous myth is the belief that we live in a democracy. Democracy may be the myth, but the dangerous lie is that we have already achieved it. If democracy is a means to an end, we need some consensus on what that end is. Good governance? What does that mean? What values are we prioritizing?”

— Malka Older, Author, Humanitarian

The burden of democratic participation

- Democracy is hard work, and often “punishingly inequitable.” Because of the requirements of time, money, and attention that go into democratic participation, a significant and often unjust barrier exists between those who can frequently and deeply engage in democracy, and those who cannot. As it is practiced, especially at the local level, “if you don’t show up, you lose.” Political participation can become a war of attrition and attention.

- Moreover, the work of democracy is never finished. That is why the development of a culture of democracy is critical. Democracy is not just about racing to the next election, but about movement-building, coalition-building, and the glorious uncertainty of what comes next.

“The key to good democratic governance…is designing how much cognitive load and attention is required of citizens, and not just thinking if democracy is good, then more and more is better.”

— Christopher Cabaldon, Former Mayor of West Sacramento, CA

The spectrum of democracy

- One should not think in terms of more or less government, or more or less democracy, but rather what are the differences in ways to make decisions, participate, and take collective action.

- Democracy advocates often “fetishize individual choices” often at the expense of broader, collective, systemic issues. Individual choice is part of democracy, but accepting that you can’t always get your way, and maybe you shouldn’t get your way so the greater good can take precedent, is often underemphasized in democratic discussions.

- Liquid democracy is a proposed hybrid form of direct democracy wherein citizens would be allowed to vote on each proposed legislation within their jurisdiction, or choose to allow a proxy voter to represent them. This proxy could be assigned on a case-by-case or vote-by-vote manner. For example, if environmental legislation is up for a vote, you could assign your vote to a climate expert who represents your opinions. This proxy can be assigned and rescinded at any time in the process.

“Democracy is not just about fair elections. It’s about people learning to collaborate across differences in all spheres of life.”

— Trygve Throntveit, Minnesota Humanities Center/Institute for Public Life and Work

The speed of democracy

- Representative and deliberative forms of democracy create many “speed bumps” on collective decision-making and execution of decisions. Presidentialist systems with divisions of government function (like the U.S. system) require multi-stage debate and voting from disparate bodies. Parliamentary forms of government (like the U.K. system) reduce these choke points and often allow for a more agile system. Parliamentary systems reduce what has been called vetocracy—wherein an individual or minority representative group can bring legislative or governing processes to a halt.

- Participants mentioned the potential deployment of automated systems to increase the speed of governing. Imagine laws being “downloaded” into technology and the built environment automatically.

- This would reduce the amount of time to implement laws and regulation, and it would increase the precision of enforcement of many laws. Of course, the impact on individual freedom and human discretion in enforcement would be massive.

- Another domain of faster, automated governance could be with sentiment analysis of constituents’ expressions and inferred preferences. Social media analysis could indicate voter satisfaction with elected officials or laws and regulations without without requiring citizens to express these feeling directly at the polls, town halls, or city council meetings. This automated feedback loop could be useful for elected officials who are trying to understand voter sentiment, and for citizens to have their voices “heard” without the burden of extra democratic effort. This could lead to what one might call a more casual, or habitual democracy.

“Democracy is a mechanism. It has a rhythm and a dynamics. But the acceleration of time changed the nature and the DNA of the process.”

— Francisco Gaetani, Getulio Vargas Foundation

The place(s) of democracy

- Where democracy does and does not take place is a key variable in understanding civic health. As mentioned above, the burden of participation is one of time and place, which is tied often to money and power.

- With increased migration of people due to climate change, wars, economic needs, and the increase in remote work, the challenge of governance for a more nomadic and temporary constituency is significant. Can representative government account for the more temporary, fragmented, nomadic movements of people, and is governance always required to be tied exclusively or directly to geography?

- Centralized locations, like city hall, offer the benefit of predictability and control. We know when and where these public meetings will take place, and there is an understood process in place. However, these centralized locations are not equally accessible, and they can be overwhelmed by aggressive participation around certain issues. All the energy in one place can be good and bad for democracy.

- Decentralized locations offer much greater access for more people (think social media portals or location-based sounding boards), but there is less direct access to representatives, and the messages of citizens can feel inconsequential or lost in the cacophony.

“Social networks give us the simulation of democratic participation. The damndest thing about the simulation of democratic politics in social media is that, while democratic politics are slow and frustrating, social media gives us that quick dopamine hit through likes, retweets, instant gratification. Basically takes our participation and makes it an impotent pinball game.”

— Jared Yates Sexton, Georgia Southern University

Conclusion: Building Civic Muscle

- Space, speed, labor, and flavors of democracy are all tied to the fundamental relationships between individuals and the collectives within we exist. A point that is often lost in the framing of these two poles as opposites, or in conflict, is that individual circumstances can be (and have been) greatly improved by collective action. Advocates of democracy must do a better job of showing individuals the personal benefits they gain by cooperating and coordinating with others, and by sometimes subverting their own needs for the good of the group. With a long-term view, individual quality of life increases when democracies are healthy.

- It is no surprise then, that one of the most compelling metaphors for the expert participants was the idea of “civic muscle.” In this metaphor, one can see that democracy is not an abstract end state, but a mode of being, a lifestyle, a habit of collective behavior that can be strengthened with effort, or that can wither away from non-use. It takes effort to workout, but that effort is rewarded with better health and well-being.

- It seems that our civic muscles have atrophied of late, but opportunities for rehabilitation abound, and the will to use democratic institutions to create a better world is still strong.

Acknowledgements

Author: Jake Dunagan | Ph.D.,

Director, Governance Futures Lab, IFTF

Contributing Researcher: Ilana Lipsett

Senior Program Manager, IFTF

IFTF and NDI would like to thank our expert participants for their insights and contributions to this report.

- Christopher Cabaldon | Mayor in Residence, IFTF

(former Mayor of West Sacramento, CA) - Francisco Gaetani | Getulio Vargas Foundation

- Jared Yates Sexton | Professor, Georgia Southern University

- Nils Gilman | VP of Programs, Berggruen Institute

- Rebecca Shamash | Director, Equitable Futures Lab, IFTF

- Malka Older | Author, Humanitarian

- Joey Siu | Policy Advisor, Hong Kong Watch

- David Adler | General Coordinator, Progressive International

- Frances Hui | Multimedia Journalist

- Trygve Throntveit | Global Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Institute

- Alex Ebert | Musician, Activist

About Institute for the Future (IFTF)

Institute for the Future (IFTF) is the world’s leading futures organization. For over 50 years, businesses, governments, and social impact organizations have depended upon IFTF global forecasts, custom research, and foresight training to navigate complex change and develop world-ready strategies. IFTF methodologies and toolsets yield coherent views of transformative possibilities across all sectors that together support a more sustainable future. Institute for the Future is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Palo Alto, California. iftf.org

About National Democratic Institute (NDI)

NDI is a non-profit, non-partisan, non-governmental organization that works in partnership around the world to strengthen and safeguard democratic institutions, processes, norms and values to secure a better quality of life for all. NDI envisions a world where democracy and freedom prevail, with dignity for all. ndi.org

This content was developed by the Institute for the Future (IFTF) under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license (CC NY-NC-SA).