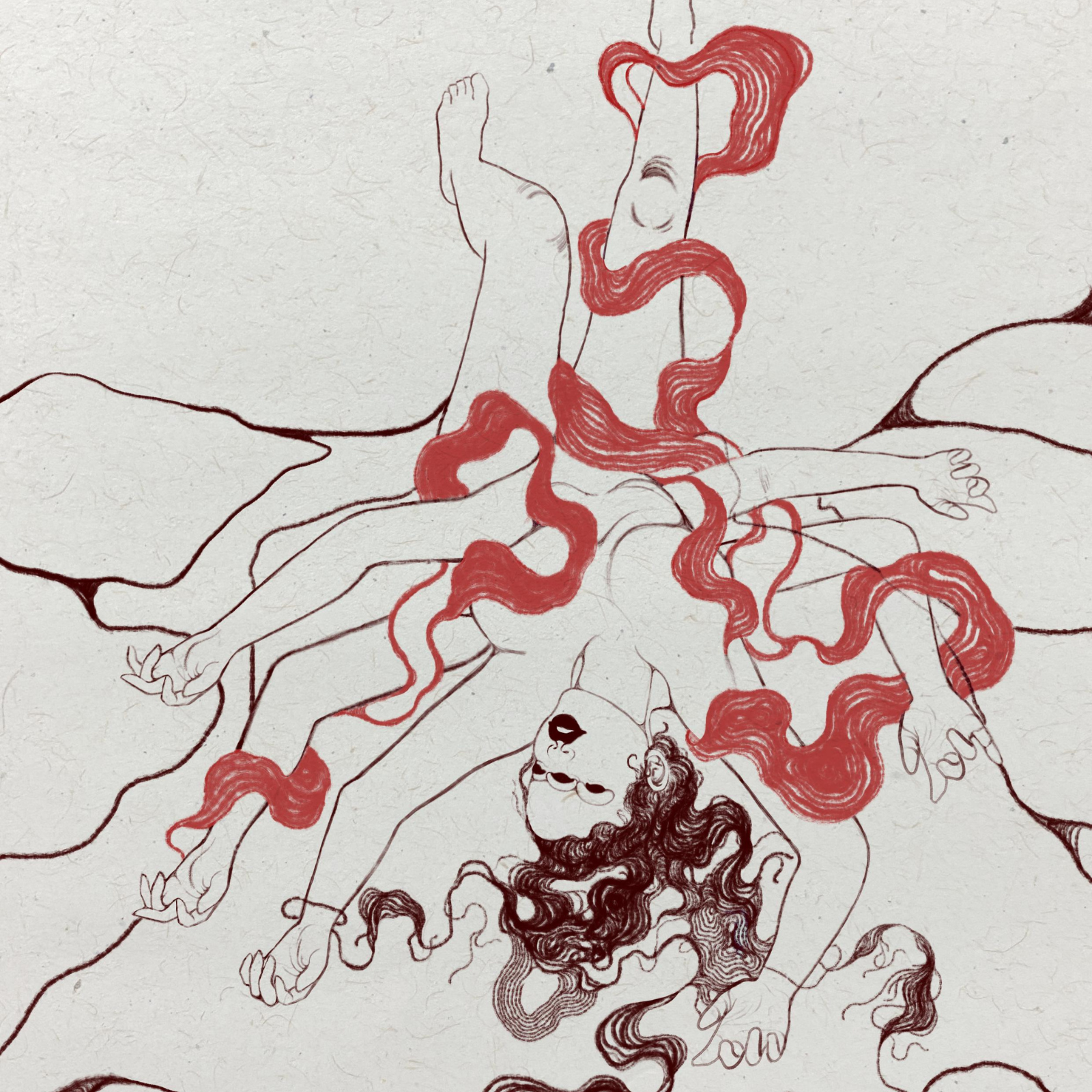

Here lies the queen, giant and still, each of her six arms sprawled open, curved, twitching like she has forgotten she no longer breathes. Here, in the royal chamber, among us who only know how to serve, a goddess instead of a woman, a creature so gargantuan that not even dozens of us could move her, she who covers all, whom we have fed since she was born. We who transformed her into what she is and what she has been admire her now, not knowing how to continue without her orders telling us what to do and where to go.

Some approach her. The queen’s body refuses to rot, frozen in an eternal chrysalis, firm and dry, highlighting what we should have already known: she is grotesque. Lying on comfortable pillows, the queen rests facing the ceiling, her two upper arms extended in martyrdom, her central pair folded unnaturally, her legs propped against the walls.

The Great Mother is dead, some of us say—our whispers echoing inside the chamber. Others clean her body, wiping the soil and dust off her articulated limbs, polishing the terracotta hue of the royal corpse. The neck ligature of the former ruler has been split, almost entirely amputated, and doubt spreads among us: the stripes of organic tissue look like they have been slashed, a poorly executed decapitation, perhaps. The question remains: what will we do now?

We only hear our own echo for days. Without the duty of work, we aimlessly roam the complex tunnels we have been building for years, and wander the fungal gardens we lovingly cultivated, turned into nothing more than entwined white carcasses. In the nursery, the children toss and turn without the food we used to deliver without fail. The underground booms with the queen’s title—the Great Mother—and we cover her chamber with leaves as dead as her.

“There is no reason to leave the body here,” says Vinca, walking amid the barren fingers of our monarch. “The royal chamber is far larger than the others. It could house two or three nurseries.”

“What is a nursery for, without offspring?” we ask. “Only the queen can give birth to new children.”

“An archive, then,” says Vinca.

“What is memory without its people?” we answer back. “What are we, without a leader?”

“Or a plantation.” Vinca climbs the phalanges of the deceased, walking over the joints of the arm and stopping above the thorax. “It could be greater than any garden. With the humidity and the space we have here…”

“Why cultivate, if we are already dead?”

Vinca gazes down at our mother. The queen lies naked, like she always was on her sumptuous pillows, partially covered by the crimson fabric that spirals from her breast to the middle of her inanimate legs. It makes the body look like the body it should be: beautiful, maternal, immaculate, immense. For a moment, that is how we see her: ephemeral, not the end of our lineage, not an announced calamity, not the imminent destruction of our anthill that now decays without new life.

She is nothing but a body.

The realization is transmitted through our shared network of minds. Our mother is just a body; she is not divine. We keep no secrets from each other—we should keep no secrets—we cannot have them. We are more than individuals, we are the web that ties us, the internal skeleton connecting every dot of this colony, where visions and opinions drip without explanation from one sister to the other, streaming from the same infinite source. We have no secrets, but the queen remains dead, and no one knows who killed her. The grief that controls us is not for her, but for ourselves. The desire to live is a thirst; it burns in the throats of our guttural tunnels; it twists the bodies of our children, who cry and plead for attention, activating a mechanism unknown until now: that of the most primal instinct, urging us to survive.

In the nursery, we hear another voice.

“Do we have any princesses? I could swear I saw one or two of them, the other day,” says Hosta, huge compared to so many others, but still childlike in front of the queen.

“There are none,” we answer. “The queen ate them all.”

Hosta’s muscular arms are not made for the young, and her mandibles are heavy and inept before the pale newborns. She touches one of the grubs, whose thin, translucent pellicle is yet to crystallize in the shape of an adult, and the girl wriggles like she has been burned. There are cradles of baked clay scattered across the room, thousands of them that go from the floor to the ceiling, tiny holes hiding equally tiny creatures.

“Excellent.” Hosta sets the baby aside and returns to the center of the nursery, where we observe her, as fearful of her harshness as the children are fearful of her size and strength. “If you happen to find one, she must be fed like all the others; she must be raised like all the others, without privilege or special conditions, independently of what she eventually becomes. Do you understand?”

The nursemaids nod.

Those squalid old women surround Hosta, peering at her from the gloom. Something changes within us. In the depths of our home, there are factions that agree with Hosta, while others side with Vinca: why not repurpose the royal chamber? Why should we have another queen? Hosta tears a piece of crimson fabric and ties it to one of her six sinewy arms, and her supporters mimic her, weaving linen and dyeing it with annatto for their own armbands.

Vinca does the same, but instead of tying a red crest around her arm, she covers her narrow shoulders with cloth, an improvised scarlet shawl. Her companions, all of them quick and small-framed workers like herself, paint their exposed thoraxes with the same shade of red ink.

We agree; we disagree; we doubt. We do not know who is wrong or right. We do not even know if Vinca or Hosta have the right to complain or suggest, but their words spread like a forest fire. We who have dearly revered the queen now see her vacant and untouched shell and her long, symmetrical arms as a threat. We who braided the waves of her antennae leave the threads unfurled on the ground, countless brown roots coming out of her regal head.

She who birthed and governed us, who chose which of us were most fitting to serve her; which were too old and should be banished to the nurseries; which were relegated to manual labor; which should dig more and more tunnels that branch into more and more chambers. All from the comfort of her pillows, tall, melancholy and silent, never even bothering to speak. She just lifted a finger, and the order was branded in our heads and extended to our comrades: you, strong one, to the squadron. You, architect, mold clay. You, servant, mine.

Our minuscule sisters crawled over her chest, covering one breast with cloth, braiding the antennae that grew longer each year, reaching miles in length. Her three compound eyes, dark and red like the soil of our home, never looked at us, not even once.

Another idea rustles the colony.

“If we want to save the garden, we must bring in new apprentices,” says Sienna, one of the few elders who works outside of the nurseries. She has a missing leg, but we have carved her a wooden replacement with almost perfect articulations covering the embedded mechanism. The prosthetic limb is pale compared to her rutile complexion, but it allows her to move more freely. “I would like to call some of the squadron girls, since they have so many reserves sitting around.”

The gardeners exchange glances. The ones sucking the fermented wine from sculpted pipes raise confused faces. The ones pruning the longest twigs of the yeast bushes set their tools aside. The ones plucking the delicate bioluminescent mushrooms that light up the underground freeze, their hands rigid around the flat caps or the stems that keep them still.

“The squadron can only do what it was born to do,” we say. “They are strong, nothing else.”

“They only know what they learned to know,” replies Sienna. “They have been told they are big and sturdy, so they fight. But they have arms like ours, and they are as capable as we are of comprehension, attention and care. We can teach them.”

“Not everyone knows how to learn,” we insist. “Not everyone wants to.”

Sienna walks under the fungal lanterns, bluish sparks shimmering above her head. Her skin is tough and shriveled like leather because of her age, her skilled fingers are scarred and fragile. The tools have marked her body, excavating grooves like those of a chiseled trunk, and her limbs have burn scars from the acid of other women’s bites and the toxins of some of the species she farms.

“Everyone can learn. Everyone has the right to try.”

“The nursemaids are too old to learn. The guards never come down to the chambers; they stay above ground, patrolling, watching a planet that is not ours. The maids were designed to clean waste and serve the queen.” The multitude of voices reverberates through the spiraling paths of the anthill. Vinca and Hosta raise their heads, hearing the exchange even from far away. “If we stop being who we are, we are lost. If we change, we die.”

“Then we can burn the garden, bury the tunnels, and close the entrances,” says Sienna. “If we remain as we are, we are already dead.”

Change terrifies us. It always has. Fear runs free through our maze, and with it the expectation of what is to come. We expected that our mental network of memories and knowledge would be sufficient; that the fabric of every colony that existed before ours, the lineage of queen after queen leading to our dead monarch, would tell us the exact solution to this equation. It does not. Here we are, dizzy, divided between three influences and none. Little by little, we can feel our companions walking away from the mother mind, thinking outside the invisible web that follows us.

Deserters walk down the corridors painted or dressed, always in red. Royal red is now known as communal red: the color that the workers use to sculpt a new room, the shade that embellishes the stairways to the exit of the anthill, the thread that sews the leaf awnings around the sentinel tower. We cover the children with scarlet bedspreads and label the mushrooms that need to be transferred with annatto.

Without the safe embrace of the superorganism, Vinca feels lost. She never wanted to be a leader. She longed to criticize, yes; she dreaded the Great Mother and the way she sacrificed the workers for the colony. She could not stand to see her surrounded by servants fanning her with leaves, or with the juice from the fruits collected by gatherers dripping from her hypertrophied jaw. She yearned for the day they could all share the perishable goods found on the surface, or the moment they would sleep in spacious and comfortable chambers, like the queen did.

She had no wish to replace her.

Vinca walks out of the shadows of a corridor after hours searching for a moment where she and Hosta can talk alone.

“Despite everything, we agree.” Vinca says. “I don’t want them to choose another queen. In fact, I don’t want anyone to look down at us from above.”

Hosta stares at her. As a manual worker, the small, agile, and precise Vinca is almost helpless facing a ranger from the platoon. Her brown antennae are tied with a red strip of cloth woven into the braid that rests on her shoulder. Her narrow waist disappears under a shawl. She squares up her six limbs, alarmed.

“Maybe so,” answers Hosta. “What if we do?”

Vinca stares back. Hosta with her short antennae, her five tiny eyes, her rough and hardened face. Hosta with an old scar cut deep into her forehead, the spoil of a successful battle against invaders. Hosta with red bands around her wrists, red cloth binding her chest. She could attack her, but she will not. She could devour her, but she will not. The superorganism imprinted the good old survival instinct in all of them.

“I also heard that you agree with repurposing the royal chamber,” continues Vinca. “Do you have any suggestions on how to deal with the body?”

“If I were to choose, I would chop her in pieces and feed the nursery with the remains.” Hosta’s voice is fierce, and Vinca tries to pull away when the other woman grasps her by the wrist, twisting one of her articulations, her own arm thin as a twig. “Not everyone seems to agree.”

Vinca clicks her jaw, thoughtful.

“The division between us worries me more than the purpose of the chamber. If we continue like this…”

“If we continue like this, we die,” finishes Hosta, releasing her. “Is that so?”

“The others are still prisoners to the affection they felt for the Great Mother. Or, perhaps, the affection they feel for our history…” Vinca forgets their previous animosity, and feels the drastic urge to throw herself in Hosta’s arms. She realizes, at last, that she has been abandoned by the intricate mental net that unites us. She lacks the solace of our biological connection, the tranquility of exemption. She has to make her own choices and reach her own conclusions. Not even the ancestral traditions woven into our genetic code seem accessible to her, and all she has left is an equal: Hosta. “Maybe that’s the problem. The others also matter. We need to hear what they want and, perhaps, concede what needs to be conceded. If the price of no longer having a queen is keeping the memory-body, so be it. We can make this small sacrifice.”

They exchange looks. Hosta knows she has been repelled by the hive consciousness too; and, as hard as it is to admit it, she feels the lack of structure in her thorax. She seizes Vinca’s face, touching foreheads and antennae. Equality is comforting. Yes, it is still possible to have what they had before the loss.

“Perhaps, then, it is time to ask,” admits Hosta. “But where do we begin?”

We can feel our stray sisters coming back. We hear their steps, ascending the narrow tunnels, crossing hollowed rooms. And, as they walk to the fungal garden to speak to Sienna, we all murmur a distant song, marching toward the royal chamber.

Sienna teaches one of the sentries how to make the yeast rise and turn it into bread, while her aides show a pair of nannies where the bioluminescent mushrooms should be placed.

“We prefer to keep the lights on the nursery floor to keep the children from waking up; in the headquarters, we put them on the ceiling to illuminate the barracks as much as possible.”

Hosta and Vinca call Sienna in hushed voices, like they know instinctively of our congregation in the middle of the anthill. Maybe they hear the vibration of our steps, or maybe the fragments of collective mentality are saying come back, come back, come back. Our song resounds in the excavated channels, echoing the chorus of thousands of voices like a heart pumping hemolymph.

“Indeed, the best we can do is decide together,” agrees Sienna, her two right hands taking Hosta’s arm while her two left hands take Vinca’s. Age has made her warmer than most. “We were all born here, and the ones who were not were raised here. If the Great Mother has left us any inheritance, maybe it is this place.”

United, the three of them go on the same pilgrimage to the royal quarters. They leave the fungal garden, cross the construction rooms, the nursery, the tunnels that serpentine out of the barracks, the stairways that lead to the turrets. At last they find us, and we make way for them, our many bodies moving like one.

The queen remains in the same place we left her, but the spasms are gone. Someone arranged her harmonic limbs over the pillows, forever trapped in a deep, peaceful sleep. There are so many of us that we pile over each other, crawling on walls, pushing elbow against elbow, sitting on the legs and the torso of this perpetual mother.

The coils of her antennae are adorned with leaves, and her slashed neck is covered by a garland of shimmering mushrooms.

They do not need to call nor beg for our attention. The heavy jaws of the platoon rangers click, making sound resonate in our cave. The lights flicker. The nursemaids brought the children, the gatherers left a trail of plants and pieces of meat on the ground. The workers are stained with soil. Some have painted themselves with red dye, others have not. But all of us, even the once expatriated ones, are connecting to the ocher web of our singular mind.

The queen is dead, and we only understand it now.

Without the queen there are no offspring, but some of us remember other lives, when workers managed to replenish the nursery with children. We do not know how, not yet. It is not a problem. Together, we will build patience.

Even without these possibilities, we have living children. Daughters who wriggle, demanding attention, our little starving mouths. We have sisters who learn, who are more than the limits once imposed on them. The garden spreads through the corridors, invading other chambers, benign. The gatherers know what to bring to enhance it; they even know how to modify the species we already have and add others to the existing crops. The aides want to follow them to the surface. We have never seen it, they say—we say.

Just keep the Great Mother down here, we ask. The empty womb from which we came. Do not give us a replacement; we require none. We want what we always wanted—what we always have when we are together. Each of the giant arms is a memory we keep. Maybe it is the embodiment of the archive Vinca envisioned. The spiraling antennae remind us of what we once were. They remind the servants who cleaned, fed, and spoiled the queen, and say: never again. They remind the gatherers who sweated and struggled on the surface to bring offerings to the queen: work should not be a sacrifice.

They remind the nursemaids who were banished to constant darkness: aging is not the end of life. They remind the squadrons who invaded the colonies of our enemies and defended us from attacks: the time to kill and die is past. They remind the gardeners and the archivists that knowledge must be shared. They remind the workers that they deserve the comfort of the chambers they carved by themselves.

Mandibles are clicking.

The anthill belongs to us, it always did. The anthill belongs to our daughters. It extends across all land that we step on, all clay we mold, all seeds we harvest. It runs through the fructified veins of the garden, it condenses in the marmoreal truffles that feed us. It constitutes our articulated bodies, our intertwined existences. The chorus quiets. The hive reminds us that we are not just a swarm; we are our own organisms. One by one, we look at each other, understanding. Commitment is a laborious burden; never before have we been forced to carry its weight.

Individuality is intolerable, but thinking for everyone at all times is restrictive. The queen, reclined on her pillows, remains lifeless. Vinca holds a jug full of honey, once forbidden to all except the royals, and Sienna shares generous portions of sugary nectar in braided leaf bowls. Hosta grabs her own basin and stares at the exhausted face reflected on the viscous amber surface. Her compound eyes, her cropped antennae. When she realizes there is little left for Vinca, she cups her fingers and brings the honey to her companion’s mouth.

“We changed,” all of us sing, sitting around a circle. There is much to debate, much to learn, much to express. “We changed, we will keep changing, we will always change.”